Venture clienting sounds straightforward: find a startup, buy the solution, implement at scale.

The gap between that promise and reality is where most programs die — in procurement mazes, silo conflicts, and pilots that succeed but never leave the sandbox.

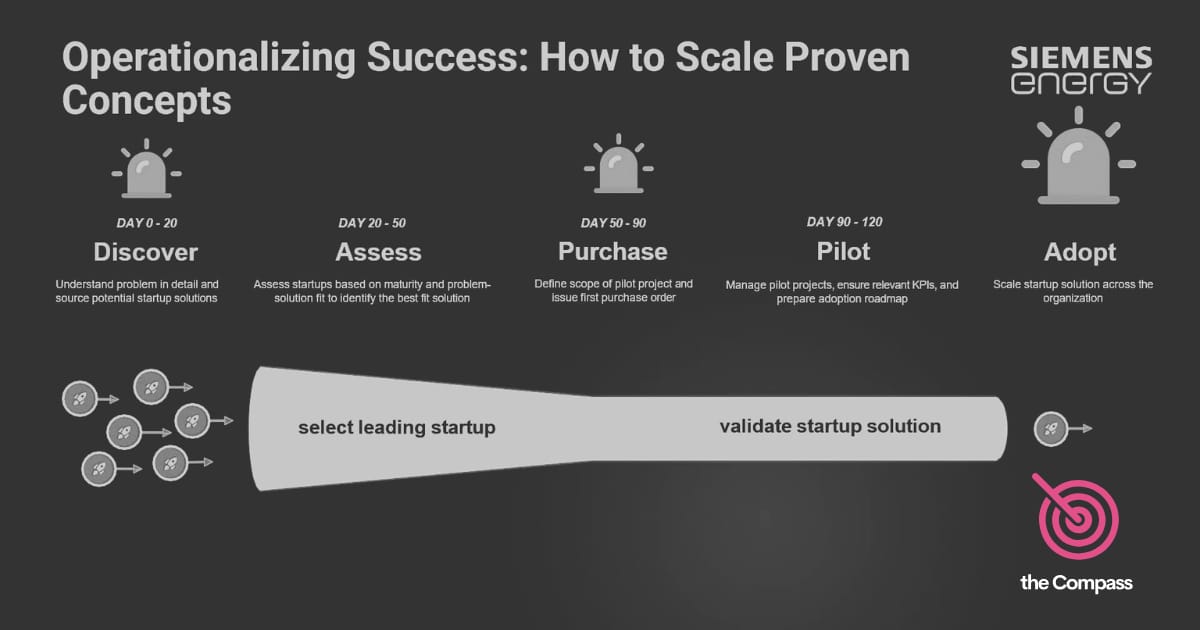

The process looks linear on a slide. In practice, it is a series of checkpoints where organizations either catch the problems early or spend months wondering why nothing scaled.

Silke Grimhardt, Lead Venture Clienting at Siemens Energy Ventures, maps where the friction lives and what it takes to get past it.

To check the full session recording, upgrade to Premium

Zebras, Unicorns, and Black Sheep

Understand your startup ecosystem before you engage

You cannot simply ask procurement to go find a startup. Startups are not a monolith, and knowing who you are dealing with matters before you commit to anything.

The landscape breaks into three types. Zebras want to grow sustainably — steady, long-term focused and maybe one day become a family business. Unicorns want to move fast and scale hard. And then there are the Black Sheep: the startups that promise much but don’t deliver.

The black sheep problem is what makes the venture client model necessary. When a startup solution gets integrated into enterprise operations, the organization builds a dependency on it. If the startup over-promised on what it could actually deliver, that dependency becomes a liability. The venture client model exists to test the solution in a controlled pilot before any deep integration happens, so that by the time the organization commits, it knows what it is actually getting.

You cannot risk integrating a solution deeply into the enterprise based on a pitch deck alone. "That is why you should go out there and test the startup solution first, and that is why the venture client model comes in place,” Silke says. The model acts as a filter, allowing the organization to test the solution in a controlled pilot before committing to a long-term marriage.

Why the Model Breaks

Even with a clear definition of venture clienting—buying the product, not the company—the process often fractures. Three specific failure points prevent the model from delivering value:

Innovation Disconnected from Business Need

The most common trap is the "cool factor." Innovation teams often fall in love with a technology or a startup's vibe without verifying the strategic necessity. "Maybe you just work with a startup because you think the startup is so cool, or you want to try something out, but there isn't actually a strategy fit to it."

Internal Resistance and Silos

A venture client unit cannot operate in isolation. It relies on the machinery of the corporate host—legal, procurement, and IT. You need to really work with procurement, with legal, you need to really make it match.

Silos create redundancy. Without central visibility, different business areas might pilot different solutions for the same problem, or even worse, work with the same startup independently.

Pilots That Don't Scale

The pilot is not the destination; it is the bridge. Yet, many projects end at the bridge, as they can’t scale. If the solution works but never leaves the sandbox, the model has failed.

The Process: Preventing "Garbage In, Garbage Out"

The standard process follows a clear flow: Discover, Purchase, Pilot, Adopt. It looks linear on a slide, but in practice it is a series of checkpoints designed to prevent low-quality inputs from becoming low-quality outputs. If things go wrong at the start, nothing great comes out at the end.

The Discover Phase: The "Yes, No, Hell No" List

The first point of failure is the problem definition. Innovation teams must act as investigators, interrogating business units to validate the reality of the pain point. A rigorous set of questions includes:

Have you worked on this problem before?

Do you know any existing solutions?

Do you actually have a budget?

Is this something you want to address now?

The budget question is a critical gatekeeper. No budget means no commitment, and no commitment means the pilot will stall before it starts. Urgency is the second gatekeeper. If a business unit owner says the solution can wait a year or two, that is a signal to move on and find a problem that actually needs solving now.

The Purchase Phase: The Friction of "The Match in Heaven"

Once a problem matches a startup solution, the "match in heaven" meets the reality of corporate purchasing. This phase is fraught with legal and structural roadblocks.

Traditionally, corporations dictate terms. The market dynamics are shifting. Startups are becoming more protective and less willing to sign standard corporate boilerplate. That’s why it’s important to make the NDA-process as startup-friendly as possible, and investigate where the pushback is coming from so the process can be adapted before it becomes a blocker.

In global organizations, procurement is a labyrinth. The complexity of global versus local jurisdiction can paralyze a pilot. Understanding whether a purchase requires German procurement, US procurement, both, or neither takes time and tenacity. The mindset that works: even when everyone says it cannot be done, treat it as a problem to solve rather than a wall to stop at.

The Technical Reality: IT and Cybersecurity

Before a pilot can launch, it must survive the internal IT culture. In engineering-heavy companies, the bias toward building internally can lead to redundancy. Innovation teams must verify that the startup solution is not competing with a tool the IT department is already developing.

Cybersecurity adds another layer of complexity, particularly with AI solutions. Pilots often run on dummy data to get through initial checks, but scaling requires real integration, which triggers full security assessments that can take months and that few people know how to navigate. Appointing a dedicated person to manage those assessments and building a manual for the process helps cut through the ambiguity.

The Pilot and Adoption: The Adoption Cube

Interestingly, the pilot is often not the biggest problem, because then everything is set, they just run. The real challenge resurfaces when the pilot succeeds and needs to be integrated.

Scaling a solution from one business unit to multiple areas creates exponential complexity. You really need people who understand how the whole company works.

To manage this, you can utilize an Adoption Cube—assembling a team of "adoption owners" who are dedicated people from crucial functions helping bring the startup into the company. Checklists and structured community support help streamline the process.

Solving Puzzles vs. Collecting Pieces

The venture client model is about changing the organizational mindset, moving from isolated experiments to strategic integration.

"When you use venture clienting in a good way, it can really help you to align your innovation with the business needs."

It bridges gaps between business areas and accelerates the speed of operation.

Ultimately, the success of the model depends on how the organization views the effort. The defining question remains: "Are you solving puzzles or just collecting pieces?"