On average, corporations hold more capital than ever before: a staggering $7 trillion sits on U.S. corporate balance sheets alone. Despite this massive accumulation of resources, companies are going out of business at an exponential rate.

Often, we assume that more money equals more security. But Elliott Parker, CEO of Alloy Partners, argues that we are fundamentally misunderstanding the mechanism of corporate survival.

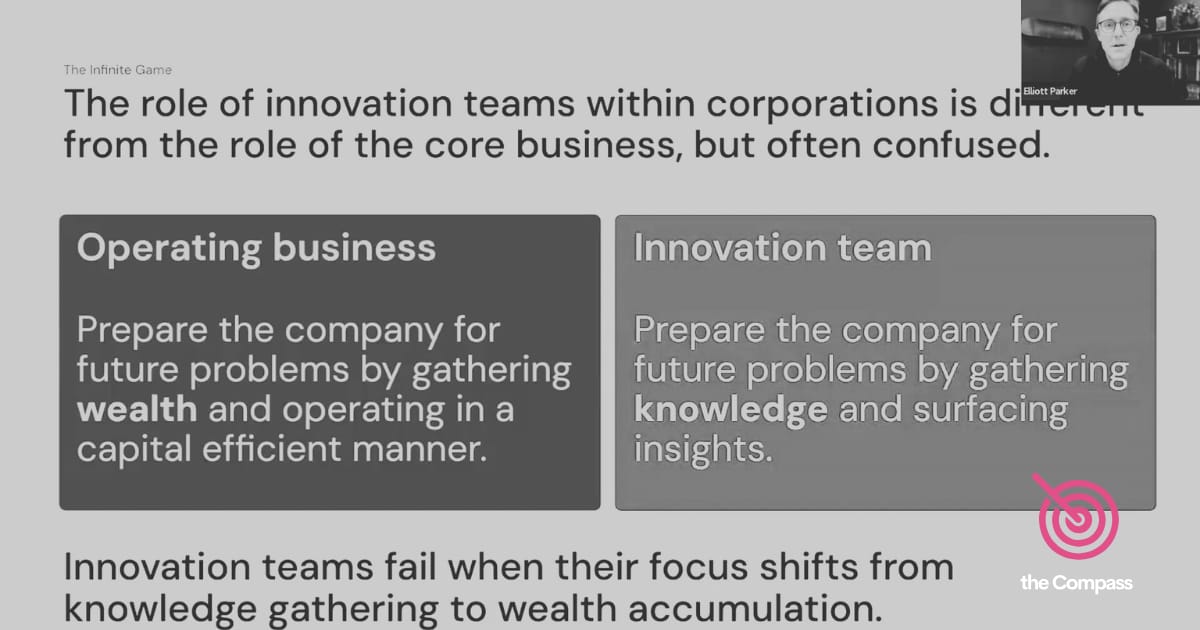

We are optimizing our organizations for capital efficiency - gathering wealth - while failing to optimize for the one thing that actually ensures survival: gathering knowledge.

To counter this, we must view our innovation teams as players in the “infinite game,” generating data about the future that the core business cannot see.

To check the full session recording, upgrade to Premium

The Infinite Game

Resilience comes from learning, not efficiency

To understand the role of an innovation team, you must first understand the game you are playing. Elliott references James Carse's distinction between finite and infinite games.

"Infinite games are played not to win, but to ensure the ongoing evolution and perpetuation of the game for the benefit of all players involved," he explains. "Business is an infinite game where the goal is to continue playing for as long as you can, as long as all the players are benefiting."

Corporations often confuse the objective of the game and that’s when problems surface. They focus on maximizing profitability and capital efficiency, assuming this creates safety. However, the shrinking lifespans of corporations suggest otherwise. "Capital efficiency is not correlated with long term resilience and endurance," Elliott underlines.

When companies optimize for efficiency, they optimize for mistake avoidance. They make operations predictable and safe. But in doing so, they fail to make the mistakes that lead to lessons, surprises, and new ways of thinking. In other words, they stop learning.

The Amazon Forest Metaphor: Decentralizing Failures to Flourish

Run cheap experiments at the edges, not the center

To illustrate how resilient systems gather knowledge, take the Amazon ecosystem as an example. The Amazon is extraordinarily resilient because it innovates through mutation at the level of cells and organisms.

In natural systems, there are no top-down objectives. There are only constraints: limited light, water, and food. Elliott argues corporations should mimic this.

"The goal for that innovation team is to run as many experiments as possible at the lowest possible cost per experiment."

Crucially, this must not happen at the center. "Experiment at the margins. Don't centralize."

Elliott recounts an innovation executive telling him, "We are very good in our company at failing slowly and at scale." This is what you want to avoid. You want failure at the margins, or at the "cellular" level, so that if an experiment fails, the ecosystem survives. But if it succeeds, the ecosystem can adopt it.

"It's very hard to predict ahead of time which insights are going to matter the most. Therefore you need to gather as many as you can," Elliott explains. "If you do it right… that novelty compounds, that knowledge compounds over time."

The result of this continual experimentation is serendipity. You uncover anomalies and surprises that challenge the status quo, converting assumptions into new knowledge that protects the organization.

Magnitude of Correctness vs. Frequency of Correctness

Innovation teams should aim for big wins, not perfect records

One of the most critical conceptual distinctions is the difference between how an operating business and an innovation team view "being right." As expected, the thought processes between the two are very different.

Inside the operating business, the culture is optimized for frequency of correctness. "Executives are promoted and learn never to be wrong," Elliott notes. They must be right frequently to maintain efficiency and predictability.

However, innovation teams should steer away from this philosophy and operate by a different set of physics. "Innovation teams should be optimized… for magnitude of correctness."

In the world of venture capital and startups, you expect to make many mistakes. "Innovation teams should have permission to be wrong a lot, as long as when they are right, the outcomes are spectacular."

This is the power law dynamic: you need a high volume of experiments because the few that work will pay for all the failures. When these two worlds collide, chaos often erupts. "We run into problems when innovation teams are given governance and incentive systems that are optimized for frequency of correctness," Elliott says.

When you force innovation teams to use the same processes, talent, and incentives as the scale organization, you strip them of the ability to uncover the spectacular outcomes necessary for resilience.

Adopting the Infinite Mindset

In a world of finite metrics and quarterly pressures, corporate innovators must adopt an infinite mindset. Elliott advises innovation teams in 2026 to focus on relentless knowledge creation over short-term wins.

Adopt Learning as the Formula for Futureproofing

Knowledge is your hedge against inevitable problems

Drawing from David Deutsch, Elliott mentions that systems—civilizations or corporations alike—ultimately collapse from a single core failure: the inability to generate new knowledge.

"Past civilizations all failed for the same reason, and they failed because they lacked the knowledge and the wealth with which to deal with problems that arose."

He explains that problems are inevitable. "We can't avoid problems." Eventually, a crisis arrives that is so significant the entity cannot deal with it. "Ultimately, a problem comes that's so big and so important the corporation cannot deal with it because we don't know how to deal with it, or we don't have the wealth to solve it."

Therefore, the formula for a resilient institution is specific: "If you want to build a resilient institution, your goal should be to gather as much knowledge and wealth as possible so that you can deal with any problem that might arise."

This distinction—gathering knowledge versus gathering wealth—is the dividing line between the operating business and the innovation team.

Make Knowledge Your Critical Success Factor

Separating the role of the core business from innovation

Corporations struggle because they conflate the roles of their internal functions. Elliott provides a sharp delineation between the core business and the innovation function:

The operating business exists to generate wealth. It does this by operating in a capital-efficient way, generating the profit needed to prepare for future problems. "The operating business is very good at gathering knowledge about the world as it exists right now”. It understands how to run the company today. However, "it is not good at gathering knowledge about the future.

The innovation teams exist to generate knowledge. "Innovation teams help corporations endure… by gathering knowledge, not by creating wealth."

Elliott warns that innovation teams are bound to failure if executives shift their focus. "Innovation teams fail when their focus shifts from knowledge gathering to wealth accumulation." A common scenario can confirm this: imagine a corporation identifies a significant revenue gap over the next three years and tasks the innovation team with closing a substantial portion of it through new ventures. This is most certainly a setup for failure. "The innovation team is not a good tool for gathering wealth."

Boldly put, asking an innovation team to generate billions in net new revenue in a short timeframe is like asking them to outperform the fastest-growing startups in history, often with part-time resources and corporate constraints.

This goal is neither realistic nor effective. "A much better goal is to have the innovation team focus on knowledge gathering and to organize your metrics and objectives and definition of success around knowledge gathering," Elliott advises. If the innovation team gathers knowledge, the operating business can use those insights to enter new markets and eventually gather the wealth.

Stop Trying To Predict. Instead, Create Data

Run experiments to learn what no report can tell you

A core challenge for leadership is the desire for data to back up decisions. But Elliott reminds us that we cannot buy reports on the future.

"There is no data about the future. The only data that we can find about the future is the data that we create."

How do you create data? "Action creates data about the future," Elliott says. "The only way we discover the future is by taking action… you take action in the form of experiments to convert assumptions into knowledge."

Take On External Validation as Your Key Metric

If VCs want to invest, you've uncovered something real

If the goal is knowledge, not wealth, how do you measure success? Elliott warns that "Bad metrics are the metrics that we use to run the core operating business," such as near-term return on invested capital. Instead, the following is suggested:

Make sure your metrics are defining how the innovation team goes and gathers knowledge. "Good metrics focus on the conversion of assumptions to knowledge," Elliott explains. They measure the speed of learning and the validation of hypotheses.

Elliott proposes a specific, high-bar metric for determining if an innovation team is truly creating value."The very best metric for an innovation team is the extent to which external corporations and venture capitalists are clamoring to invest in the things you're building."

External validation is proof that you've uncovered knowledge that the market didn't yet have. Elliott connects this to Peter Thiel's concept of "secrets." "Every good startup… has uncovered a secret about the future." If external investors—who are purely profit-motivated—want to put their capital into what your team has built, it validates that you have discovered a secret. You have generated genuine knowledge.

In hindsight, when ventures attract outside investment interest, it signals that the innovation team has uncovered something the market values. This is knowledge that translates into competitive advantage for the corporation, validated not by internal politics, but by the market itself.

Separate Efficiency and Transformation

Efficiency belongs in the core business, not your team

A common trap for innovation leaders is the pressure to deliver efficiency for the core business while also being asked to invent the future.

"You can't do both of those things at once… you can't expect transformation out of efficiency."

Efficiency innovation is important, but it belongs in the operating business. "Efficiency innovation is not going to generate the types of insights that create long term resilience for the organization."

When innovation teams are dragged into efficiency work, they stop gathering knowledge about the future and start generating savings for the present. This leaves the corporation vulnerable to the "inevitable problems" Elliott warns of: the problems that require new knowledge to solve.

Executives often want both: transformation and efficiency. Still, this pairing needs to decouple. Elliott’s advice is to be direct about this to senior leaders: "If this is what you're asking us to do, focus on efficiency innovation, let's just recognize the tradeoffs of that."

If you can get leadership to agree that the operating business gathers wealth and the innovation team gathers knowledge, the discussion about the “how” will be much easier.